We believe that being different is a good thing. We see the difference in us all, as neurotypicals, we are so individual. My question to us, why do we judge the not so typicals? Inclusion begins at home.

TAI has been on the forefront to provide transition from school after seeing the gaps after her child dropped out of formal training and to vocational school while still at the age of 13 years. Early intervention is key. The earlier we begin training Functional Living Skills, the sooner the independence begins.

Remember, what you don’t teach them, be prepared to do the skill for them forever.

We bring hope to parents. Yes, your child can learn. They can stay in class and not be disruptive. They can learn something, despite their special. Acquiring the Functional Living Skills is still learning. If all else fails, lets engage them in our communities as they hustle.

What would you define Autism as? Is it about the stigma, lack of inclusivity, or it a cultural curse? Why do we take them to churches for prayers? Or is it a curse either because the parents did something culturally wrong? So many stories have gone out there, but as a parent here is my view!

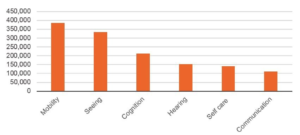

However, let’s look at the statistics from the world health organization, it is estimated that 1 in 44 children born today has Autism. According to the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS), the following figures shown below indicate that Mobility is the highest disability in numbers. However, cognition, self-care and communication disabilities combined have higher numbers than mobility. These is where you will find Autism Spectrum Disorders.

Coming closer home, the 2019 census is where we borrow our data. This information is from the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics; we look at the figures by domain. Mobility issues have the highest number at approximately 390,000, those with visual impairment at 310,000 while cognition surprisingly is next with an approximate number of 210,000. Hearing Impairment comes 4th with 150,000. Self-care and Communication where we find those with intellectual disability and Autism are at 140,000 and 110,000 respectively.

These two disabilities, Autism and Intellectual Disabilities are commonly understood to have challenges with cognition/self-care and communication. Combining the 3 figures shown in the graph show us that this is the hidden disability we are talking about. Breaking it down, we realize the numbers are not so huge, but the combined figures a much higher than those with mobility issues in our country standing at about 460,000.

We need to realize that the way we view Autism is quite different from how parents and caregivers view it. We break it down to look like the following photos in the next slide.

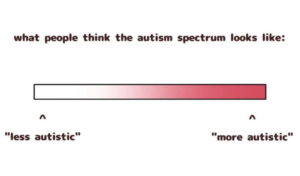

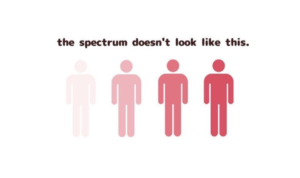

Funny how we assume that some are less or more autistic. As much as it is viewed as a spectrum, most people think of a spectrum, like the graphic below — a horizontal line that runs from “low-functioning” to “high-functioning.” Everybody is supposed to fit neatly in their own dot on the spectrum. But, that’s not how it works at all.

The left side of the bar, the less autistic side, has no color but as we reach the middle, we notice the hues of the color pink start to show until we have the more autistic right side fully colored.

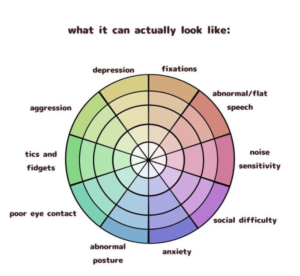

There has been so much discussion in the disability community, especially in the autistic community, about functioning labels. That’s why we have created a set of five images to explain what we mean when we say autism is on a spectrum. Below, I’ve included the images, as well as an explanation of what each means to me as a mother to an autistic person.

This second graphic is something that is becoming more common in the neurodiversity world. It illustrates how we can be very functioning in some ways and not as much in others. The characteristics reflected in this diagram include depression, fixations, abnormal/flat speech, noise sensitivity, social difficulty, anxiety, abnormal posture, poor eye contact, tics and fidgets and aggression. With this graphic, everyone can map their own personal spectrum.

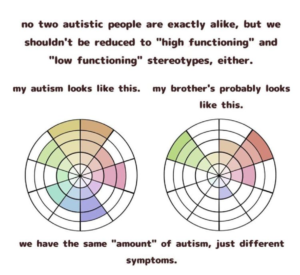

I love this set of graphics. My daughter has been labeled “high-functioning.” She’s quite good at sucking it up, and most probably due to the adapting into places such as schools, and church she has been stuck on the far right end of the linear spectrum by professionals and government agencies her whole life.

She struggles in so many areas. Her current mental state right now proves that more than ever. For 3 years now, she is suffering from one of the most severe burnouts in her life, purely because she’s tried to live up to the label of “high-functioning” every day. It is something I believe that she’s been coached and trained to do and something society expects of her too. Not many children are very lucky to have an amazing support system at home, but I have realized they keep to themselves due to either masking the wreaking havoc in their lives or trying to fit in a world that does not make sense to them at all. If I as her mother would map my daughters own autism based on this graphic, I would assume the “I’m “higher functioning” label on the creative and social skills side of the map, but pretty low on things certain things like aggression and sensory issues.

We are autistic but that is where the similarity ends. All persons generally, display different individual strengths and weaknesses. Below, the wheels includes two different wheels with different skills and struggles highlighted. The first wheel represents two different persons with autism. “We have the same ‘amount’ of autism, just different symptoms.” However, looking keenly at the image below and comparing both persons with the opposite one, we note that on the left, the persons is depressed and fixated on certain items, is quite aggressive. They are trying to be social and do not fidget not have nervous tics. On the right we find that the person is aggressive, talks in an abnormal flat speech and not too anxious. They also have good eye contact and no abnormal posture. No two autistic people are exactly alike, but they shouldn’t be reduced to ‘high-functioning’ and ‘low-functioning’ stereotypes either.

It’s worth mentioning that autism is sometimes listed as a “disorder” with “symptoms” in medical definitions, but it is not something that needs “fixing.” People on the spectrum simply experience the world differently than typical people.

Even still, I’ve loved this part of the graphic because I had never thought about autism that way, but that’s how I would urge us all to view it from now on. I have often felt like some people are not “autistic enough,” except maybe on their bad days. We would even call those their autistic days. It is freeing to realize that every day is an autistic day. Just because my daughter is stimming a lot, does not mean she has had a bad or difficult day. However, this is now taking a lot of self-regulation, but if I can let her be autistic in public and around people then being autistic equals to being herself.

What does Autism really look like?

The next image says: “the spectrum doesn’t look like this” with four people lined up, gradually becoming more pink (symbolizing the “more autistic” idea mentioned above), while the final image (below) says “we are far more,” with four technicolor people lined up (symbolizing how different every autistic person can be!).

Autism is a type of neurodiversity associated with characteristics like passionate interest in specific topics, difficulty with typical communication methods, sensory sensitivities, and using repetitive motions (sometimes called stimming) to regulate their experience.

I believe that It’s what’s on the outside that counts.

There is no genetic or blood test for ASD; diagnosis is based on purely behaviours.

Specifically, we look for three things when deciding whether someone has an Autism Spectrum Disorder as shared below. Impaired ability to interact socially with others. The person may have reduced motivation and/or skills for engaging with others. Precisely what we look for depends on their age and life-stage. During the school years, children may not seem that interested in their peers. Or they may be interested, but not know how to go about forming or maintaining friendships.

Restricted, repetitive, and/or sensory-seeking behaviours. Again, precisely what we look for depends on the person’s age. During the school years, children may enjoy activities or topics that seem very unusual (like flicking string or collecting twigs) or their interests may be age-appropriate, but overly intense. All children like to play. But the difference is children with ASD engage more intensely or in highly specific ways with their special interests, and can do so to the exclusion of other people. Some children with ASD do try to draw others into their hobbies, but don’t realize when others just aren’t that interested.

Finally, we look to see that these social issues and restricted/repetitive behaviours have been there since toddlerhood. ASD is something inherent to the child, not something they “catch” later in life.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD; which now includes former diagnostic labels such as Autistic Disorder and Asperger syndrome) is a lifelong neuro-developmental disorder.

What are the lesser known signs of Autism and how do we intervene?

Signs of Autism spectrum disorder affect people in Different ways. Some people with ASD are nonverbal, while others may speak fluently. Some people with ASD have intellectual disabilities, while others may have normal or above-average intelligence.

Autism Spectrum Disorder can cause significant challenges in communication, social and behavioral areas. There is no single cause or symptom for autism, but it is believed to be caused by a combination of various factors.

People with ASD may also have sensory processing issues, making certain sounds, tastes, smells, or textures especially bothersome or even painful.

If you’re a parent of a child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or have ASD yourself, you are probably very familiar with the most common signs and symptoms of ASD. However, there are some lesser-known signs you may not be aware of.

This can make it difficult to get a diagnosis if your child is displaying only subtle behaviors that don’t stand out as obviously being related to ASD. Here are some lesser-known types of autism spectrum disorder.

Sleep Problems

Sleep problems are common in children with ASD. Your child may have difficulty falling asleep or might wake up frequently at night. They may also have unusual sleeping patterns, such as sleeping much more or less than usual.

These sleep problems can be caused by underlying medical conditions, such as ASD-related anxiety or sensory processing issues. If your child is having sleep problems, talk to their doctor to find out if there is an underlying medical condition that needs to be treated.

Digestive Problems

Digestive problems are also common in children with ASD. Your child may have trouble digesting certain foods or may have chronic constipation or diarrhea. These digestive problems can indicate underlying medical conditions, such as ASD.

Anxiety

Anxiety is the most common autism spectrum disorder symptom in children and adults. Your child may be worried about going to school or participating in social activities. They may also have obsessive interests or repetitive behaviors that are related to anxiety.

If your child has anxiety, it is important to talk to their doctor to find out if there is an underlying medical condition that needs to be treated.

Sensory Processing Issues

Sensory processing issues are common in children with ASD. Your child may be sensitive to certain sounds, smells, tastes, or textures. They may also have trouble processing information from their senses.

These sensory processing issues can make it difficult for your child to function in everyday life. If your child is having sensory processing issues, it is important to consult a specialist for diagnosis.

Behavioral Problems

Behavioral problems are common with an autism spectrum disorder in adults and children. Your child may have tantrums or may engage in self-injurious behaviors such as head banging or biting themselves.

They may also have difficulty following rules and instructions. If your child is having behavioral problems, it is important to consult a specialist for better understanding.

We need more time to perform various tasks as explained below. Children with autism process information differently than children without it.

If you’ve ever traveled to another country and tried to navigate your days without a translator, stumbling over the local language and customs, you might just have a little glimpse into the daily life of a child on the spectrum.

Trying to make sense of a world where everyone else seems to understand each other even though the rules seem to constantly change is frustrating at best, and on many days it can feel quite demoralizing.

Children with autism experience the world this way because from early on they are wired to process information differently. Understanding how they process can help you as a parent or trainer not only better communicate with them but can also help you draw on greater empathy during life’s more frustrating moments.

What might your child say if they could articulate their struggle?

I Think from the Bottom Up. You see the forest, and Autistic child sees the trees.

This may be one of the most important things you can understand about our children with ASD.

Most of us think top-down. That means you build a big picture first, and then fill in the details, like this:

Silverware (concept)

Knife, fork, spoon. These are all types of silverware.

Shoe (concept)

Sandal, loafer, sneaker, pump. These are all types of shoes.

Dog (concept)

Great Dane, Pomeranian, Husky. These are all types of dogs.

But I start with the details, and then move outwards. So today I see something walking towards me and you say, “that it is a dog”. This something is white with spots, short hair, and comes up to my hip.

Now I think that a dog is something white with spots, short hair, and comes up to my hip. Tomorrow if I see something orange and tiny with fuzzy hair I won’t know it’s a dog unless you tell me.

Once you do, I now add that to the category, but if the next thing I see is very large with brown and white hair and a big droopy face, I might not know that it’s a dog.

I’m seeing the details first. Once I start categorizing all of these different things that count as “dog”, I slowly start to build the concept. It may take many, many examples before I understand the broader category of “dog”.

This also happens with skills. Maybe you taught me how to take turns on the swing set, but that doesn’t mean the skill will automatically transfer to the slide or even playing any other game.

This may seem like a weakness, but it’s not!

Bottom up thinkers often excel in research and data analysis, fine arts, data entry, coding, developmental biology, assembly, software testing, design, and other careers requiring detail, logic and/or repetition.

Regulating Sensory systems

The world we live in is set up in a neuro-majority friendly manner. This means people with a typical sensory system and way of thinking can most often live and thrive in the world, but people who have autistic neurology often have a sensory system and style of thinking that is not the best match for living comfortably in the world. Additionally, autistic sensory system and thinking differences pose difficulties when it comes to reading the environment and comprehending written words along with tracking and understanding conversation.

“Sensory regulation involves actively adjusting amounts and kinds of incoming sensory information in a way that allows for optimal functioning because one’s neurology does not permit this to occur automatically”

During sensory regulation the system is balanced or regulated by providing either targeted sensory input or intentional sensory guarding from input that is aimed at providing the specific balance needed at that time to regulate the sensory system. It is hard work to keep the sensory system regulated, but is a requirement to access learning in a school environment, function optimally each day and to realize meaningful life outcomes.

Understanding and expressing our emotions

This is evident in that, when asked ‘How do autistic people display deficits in our expression?’, many will say we struggle with spontaneous responses, despite being able to replicate an emotion when asked. Yet, as we study into autism and facial expression we find, it isn’t because autistic people struggle to convey emotion, but because there are two fundamental flaws in the way our responses are tested:

Autistic people are often socially anxious. Therefore, if you sit them in a controlled room and tell them to act naturally, you are going to get anything but spontaneous.

Autistic expressions have been judged on how we shape our faces similarly to others and not how the consistency of the faces demonstrate a stable response.

Put simply, this means that many will ignore the expressions autistic people present daily, instead expecting us to react in non-autistic ways because they may have seen us do so once before. Essentially, this is like asking someone to recite the entire French national anthem because you once heard them say ‘baguette’ and it can be quite crushing for our self-confidence.

Thankfully, this realization seems to be becoming better understood in recent times; with diagnostic criteria beginning to reflect that language is a two-way street. Now, when an autistic person displays an expression which others don’t understand, the miscommunication is in part everyone’s responsibility and it’s up to us all to be part of the solution.

When “Rest Is Work Too”

Closely tied to the issue of hyperactivity is the fact that the autistic child, in my opinion, does not know “how to rest” and “do nothing” during the day. It is almost as though they must be constantly doing something during the day… that the “day” is for “doing things” and the night is for sleeping… and again, that there are no “in betweens” allowed when it comes to what the child does during his waking hours.

If there is one thing I have observed with my daughter, it is that her autistic tendencies manifest themselves more if she is not specifically working on a task. During her “downtime”, when no one was actually “working with her on specific issues”, her preference is definitely to spend that time in bringing “order” back to her world, her way… and for the most part, that involves doing things like listening to loud music.

For everyone… but, especially so for the autistic child! The autistic child appears to not know how to “truly rest”, to “just relax”. Indeed, their relaxation comes from often intense physical activity in the form of running, jumping (i.e., hyperactivity), spinning, dancing, etc. As such, during the day, the autistic child, in my opinion, experiences very little rest if he/she is unable to properly process the “parts” that make up “the whole” during his daily activities. Rest – yet another area to work on!

For the autistic child downtime is not “rest” but an opportunity to slip further into the world of autism. As such, life becomes exhausting for parents who try to keep their children constantly engaged in the daily battle against autism… a battle waged every day, every hour, every minute, every second! In looking back, I realized that I was exhausted not from work, but by burn out because of all the watching she required. Most parents find they have not slept a full night’s sleep in over two years or until their child settles into a routine of sleeping themselves, ‘autistic’ to either stim or rock until they soothe themselves to sleep. All opportunities for rest, both during the day and at night, had completely left our lives. Things get better as they grow, life with an autistic child can continue to be draining and exhausting on all family members. Given what I now understand about autism, I’m glad I made some decisions I made early on.

It is especially critical to understand that special units or classes are, in my opinion, perhaps the worst thing/place for an autistic child. The child, in my opinion, would have too much downtime… and thus, slip further and further into his own autistic world. I suspect few, if any Trainers/Caretakers in a Special unit would be there, constantly engaging and caring for an autistic child, every waking minute. Special units simply don’t work that way and thus, in my strong opinion, simply don’t work for the autistic child!

Once again, I believe the key lies in teaching the concept of rest and what can be done during “rest times”… I still struggle with this one… as I’m sure all parents do. I’m not a person to take much “rest” in the first place. Yet, there are indeed times when the ability to rest at will would certainly be golden. The reality of life with an autistic child is that it is simply totally exhausting to constantly be engaging a child… exhausting for the child, and exhausting for the parent or caretaker… and exhausting for siblings as well. Indeed, for the entire family of the autistic child, and especially the autistic child himself, and in this particular work, as difficult and overwhelming as it is, there is no pay!

Engaging Special Interests

If you engage a person on the spectrum from their area of interest, or a special interest, such as trains or animals, or what they love to engage in you will find they are quite trainable people. However, they feel they were often discouraged from pursuing this during school. “It is clear to me that we are missing a wealth of information about the strengths of these individuals and what drives them. “They feel beaten down by professionals trying to fix them. That was a turning point for me as a parent and a keen observer. Is it possible to shift the focus of their education to suit them more than suit us? Is this why we find we have none following careers but we are so busy trying to fix them than work with what we have got? Rather than trying to overcome deficits in people with autism, we should now explore ways to build on preferred interests. It’s a real avenue for learning and growth, for showing their competence. It’s about bringing special interests into the forefront and using them as motivation in learning at school or at home.

Special interests are one of the most common characteristics of people with autism. Historically, some interventions for autism have tried to limit them or use them largely as a reward for good behavior. But many people with autism consider these interests to be an important strengths and a way to relieve stress. Some even expand on them to create a successful career. I believe we should not diminish this behavior, it’s a positive aspect of the lives of our children’s lives.

My nephew can tell you all about Road construction machines. He knows all of them by name and what they do! But, he’s terrified of riding them. He’s also fascinated the stars, and knows most by name. He is only 10 years old. Are we assisting him through his area of interests? Is it disruptive if all he talks about is Stars and the red moon?

I believe it’s time we started to move more with the flow by engaging special interests than by moving them or using them as rewards for good behavior.

If we can recognize the potential benefits that special interests can bring and incorporate special interests into therapies and daily life, we can enhance social skills and other functions, as well as reduce anxiety. For example, engaging in special interests can improve attention and social interactions in people with autism.

Volunteering in an empowerment centre for girls with autism and intellectual disabilities, I met a young woman who loved to sing. When she did her chores, she was rewarded by getting to listen to her favorite songs during dance time. Unfortunately, she didn’t earn that privilege very often. She had a lot of behaviors that interfered with her getting the reward. She hummed and sang in class, disrupting the others, but that was the only way she concentrated. Calming the fears within, by fidgeting through her music.

I believe training the autistic mind takes some creativity and collaboration!

Building Interests Into Education

Some schools and organizations have started to use special interest clubs as a way to help students with autism socialize around a subject they particularly enjoy. This makes a lot of sense “You and I socialize around preferred interests — you don’t join a book club if you don’t like to read. I think more and more social skills groups are doing that.”

However, more research is required.

If you’re a parent, think about what your child is interested in and look for resources related to that interest.

Move from one task to another

Activity-Shifting: Helping Kids on the Autism Spectrum to Move Successfully from One Task to Another

“My child has a big problem with making transitions at home (school too). What methods do you use to help your child with autism (high functioning) to get accustomed to switching off one activity and on to another such as moving from a game to coming to the dinner table to eat with the rest of us?”

All children must switch from one task to another – and from one setting to another – throughout the day. At home and school, shifting naturally occurs frequently and requires children to stop one task, move from one spot to another, and begin a new task. Depending on interests, some have greater difficulty in shifting attention from one task to another and changing routines.

This difficulty is due to a greater need for predictability, challenges in understanding what task will be coming next, and emotional discomfort when a routine is disrupted. A number of supports to assist children during activity-shifting have been designed to prepare these children before the transition will occur – and to support them during the shift. When shifting techniques are used, they increase appropriate behavior during shifting, participate more successfully in school and community outings, reduce the amount of time to shift, and rely less on adults for prompting.

Task-shifting is a big part of our day to day activities, as they move to different activities or locations. coming in from the playground, gathering needed materials to start working.

Similar requirements for task-shifting are found at home as well, as these kids move from one task to another, attend functions, and join others for meals and activities.

These special needs kids often do not recognize the subtle cues leading up to a transition (e.g., packing up their materials, a teacher wrapping up her lecture, students getting their lunches out of the refrigerator, and so on) — and may not be prepared when it is time to move. Also, children with ASD often have restrictive patterns of behaviors that are hard to disrupt, thus creating difficulty at times of task-shifting. Lastly, they often have greater anxiety, which can impact behavior during times of unpredictability.

How do you wrap up?

Communicate what we would like to do

5 Ways Individuals with Autism Communicate

Even verbally fluent individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) have unique methods of communication; below, we’ve compiled five of the most common ways individuals with autism communicate. We tend to think of communication as a language-based tool, however, a large portion of communication is non-linguistic, relying on body-language, gestures, and tone of voice. Let’s take a look at these communication methods–bearing in mind that we’ll primarily be discussing the social communication skills present in high-functioning individuals with ASD.

- Non-Verbal Communication

Many people affected by ASD develop little in the way of language skills, relying instead on non-verbal communication techniques. These include a wide range of behaviors, such as using:

Gestures

Pictures or drawings

Crying and other emotive sounds

Physically directing someone’s hand to an object they want

While this can cause communication difficulties, parents and caregivers often become quite adept at reading these non-linguistic communications through context clues and repetition.

- Echolalia

Echolalia refers to the repetition of phrases that people have heard, perhaps in a favorite movie or television program. These phrases may or may not “fit” the context in which they are spoken, however, they typically do point to something concrete. Parents of autistic children are encouraged to watch the programs in which these phrases are spoken to attempt to figure out what their child might be trying to communicate when they use particular phrases.

- Focusing on the Literal Meanings of Words

Individuals with some form of ASD typically have trouble understanding idiomatic language and metaphors. Another implication of this trait is a difficulty understanding jokes and humor, which often rely on a sarcastic tone to convey the speaker’s true meaning. A hallmark of the ways individuals with autism communicate is focusing on the “key words” of a sentence. One of the best ways to accommodate this communication style is to speak in simple, plain sentences without idioms or figures of speech that hide the “true message” you’re trying to convey.

- Moving from Topic to Topic

One difficulty individuals with autism find with communication is the ability to “stay on topic.” Because their minds are moving very quickly and processing many stimuli, their thoughts may seem disorganized or unfocused. However, this usually isn’t the case–unless an ASD individual has expressed the desire to stop talking about a given topic (in which case, you should definitely move on), they’re usually open to revisiting previous conversation topics.

- Speaking with no Eye Contact

The last tool we’ll look at in the 5 ways individuals with autism communicate is the fact that often they will speak with you, but will not make eye contact. People affected by this condition are highly attuned to sensory details, and looking into someone’s eyes can cause an overload of information. Some may prefer to speak with their eyes shut entirely, so as to focus only on the stimuli provided by the conversation. Understanding and accommodating this variety of communication is key to building better communication with ASD individuals.

Activities for daily living

If you are on the autism spectrum, or your child has been diagnosed with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), you might find everyday routines, tasks and activities a little more difficult.

Because of this, it can be helpful to break down daily tasks into steps that will allow you or your child to learn how to better manage, and take control, of daily routines and activities.

What are daily living activities?

Activities of daily living are the routines people undertake on a regular or daily basis, and often take for granted, these include:

Meal times: preparing and eating regularly, including breakfast, lunch, dinner.

Self-care: showering or bathing, getting dressed, cleaning teeth, doing hair and clipping nails.

Sleeping.

Toileting.

Why are daily living activities important?

Independence: if you are able to look after yourself by undertaking these key activities of living you are more likely to be able to live safely and independently as an adult.

Self-esteem: self-reliance helps with self-esteem, it feels good to be able to look after yourself without needing help.

Less reliant on others: as with the above two points, it’s an excellent goal to be able to function on your own without needing assistance from other people if possible.

Skills for life: these daily living skills are tasks that everyone needs to undertake every day throughout their life. If you can learn to undertake them yourself early, it will make life a lot easier and improve your quality of life.

Daily living strategies for people with autism

Because autism is a developmental difference, people with autism can often find it difficult to learn and manage everyday tasks, like taking a shower, getting dressed, brushing their teeth and packing their school bag; or daily chores like making their bed, or setting the table.

People on the spectrum often need to plan tasks in order to know that they are necessary, and as such, may need reminders and extra support to incorporate tasks into their daily lives.

You can help a person on the spectrum to develop these daily skills through the step-by-step teaching technique. This includes:

Ensuring they are aware of the necessity of the activity.

Breaking tasks down into simple step-by-step routines.

Teaching them each step and encouraging them through the steps daily.

Gently providing prompts to support the completion of the task.

Celebrating and rewarding success when milestones are achieved.

An Occupational Therapist can help you or your child to learn how to undertake these everyday tasks, and can give you advice about how to help yourself or a person on the spectrum to incorporate these tasks daily.

Teaching everyday skills to people with autism

The following steps will assist you in helping your child, or dependent, to develop daily living skills.

Step 1: Develop awareness

Develop their awareness of certain skills by drawing their attention to the skill that needs to be developed. Whether it be brushing teeth, dressing or toileting.

Step 2: Identify a goal

Choose an appropriate goal that suits their age and abilities. Try not to introduce too many goals to achieve at once, and start slowly.

If getting dressed in a timely way, without distraction, is a skill you’d like them to develop, you could focus the goal on getting dressed, and start by just getting them to put on one piece of clothing themselves, like a pair of pants.

Step 3: Break it down

Break down the task as much as you can, for example, putting on a pair of pants has a number of steps which lead to the ultimate goal. Including, getting the pants out of the draw, holding the outside of the waist, stepping into the pants, first one leg, then the other, and pulling them up.

You might find it useful to draw the process, use pictures or photos of the process, model the process, or show the process on a video through of how to undertake the task.

Step 4: Teach each step

It’s important to teach each step separately, so they can learn how to undertake the task incrementally. Make sure you check with their occupational therapist about the level of the task at hand, so you’re not undertaking anything that is too advanced. Doing up buttons, for example, can be very challenging for young children. You can help them to learn each step by:

Providing them with lots of opportunities to practice.

Rewarding and praising effort, every good attempt and celebrating results.

Visually showing them what to do.

Helping and prompting them throughout the task.

Recall information from Memory

Autism and Memory: What’s the Link?

Our brains are immense. Everyone’s ability to think, reason, relate, and engage with tasks is granted by their brain’s ability to process the information in their environment. Our brains store thousands of memories, but with many believing the autistic brain is differently wired, some people wonder what the connection is between autism and memory.

The memories our brains store are a key part of our daily living. Memory helps us to function in our everyday lives and to relate to others. However, some children with autism experience challenges with memory and this can impact how they relate to the world socially.

What is memory?

It’s easy to say: “well, memory is what I remember”. Rightfully so! But, for us to remember what we do, we need to be able to extract the information, and, for that information to be present, something must have happened to have placed it there. Additionally, of course, to retrieve that information, it has to have been stored somewhere. How can I remember something I never encountered? And how could I have encountered it if I don’t remember that I did? Memory isn’t as simple as we’d like to believe it is.

Essentially, memory is the ability to encode, retain and retrieve information when we actually need it.

Memory strengths of ASD

The ability to recall from memory is linked to how engaged and involved the person was in a situation. In ASD, memory seems to be least related to social and emotional experiences. The sensory experience of some individuals with autism help to encode some events into memory. Most high-functioning autistic children can recall personal events from a young age.

Which type of memory is mostly affected in autism?

A lot of research studies the memory performance of autistic individuals, but working memory seems to be most affected across the autism population. Given the criteria of ASD researchers have wondered if traits/symptoms are due to challenges in cognitive domains that working memory supports. Some of these cognitive domains are: decision-making, control and regulation of tasks, reasoning, and behavior.

Additionally, the ability to recall personal events seems to be a challenge for some autistic children and individuals. Some researchers believe that high-functioning autistic individuals thrive in this area as, compared to low-functioning autistic individuals. This type of memory recall is known as autobiographical memory, which is the ability to recall events from our personal experiences.

Below, I unpack working memory and autobiographical memory and consider why these two types of memory might be affected in children and adults on the spectrum.

Working memory

Executive function describes all the cognitive processes in our brains and this includes working memory, impulse control, inhibitions, planning, initiation, and termination of actions. Working memory is important for human cognition and is central in executive function.

The reason why executive function is believed by scientists to be challenging for children or adults with autism is because, firstly, some autistic individuals struggle to engage in purposeful and independent behavior, as well as store and export information held in long term memory. Secondly, since working memory helps us to navigate complex and high-level cognition such as language comprehension and long-term learning, reasoning, reading comprehension, and problem solving, the observation that some autistic children find these tasks challenging suggests there is some form of executive dysfunction.

Other than challenges in cognition, working memory challenges in some autistic children and adults are associated with learning disabilities, difficulties in behavioral regulation, focusing and sustaining attention, and abstract thinking, to name a few.

Of course, these observations do not apply to each individual on the autism spectrum as symptoms differ from one individual to the next. Working memory is a complex domain of our brain and, even though we have a vast understanding of how our brains function, there’s still much that remains unknown including what makes us who we are and why we behave the way we do.

we advocate for the inclusion of the Autistic child in the classroom, not in the special unit. Keeping the child engaged, through specific interests, being creative in class is a good way to engage them. Parents should take the lead in education and special interests and be the guide to the teachers towards a better learning methodology for the child.

Can they learn? Interacting with them, and being a parent, has taught me that patience and understanding bring us all to the table.

More than Activities for Daily Living (ADL’s) taught in our schools here in Kenya, the inclusion of more Functional Living Skills training is a welcome relief to our parents, caregivers and trainers. The missing link in training and equipping the child towards pathways to independence. The Assessment of Functional Living Skills (AFLS) is a criterion-referenced skills assessment tool, tracking system, and curriculum guide for teaching children, adolescents, and adults with developmental disabilities the essential skills they need in order to achieve the most independent outcomes. Educators, professionals, and parents/caregivers using the AFLS report positive results almost immediately.

Distinctive in its simplicity and affordability, AFLS was created with one goal in mind – to help learners gain the skills and confidence they need for functional living. There are a multitude of opportunities for learners with disabilities to be active members in their communities. These abilities become reality when using the AFLS independent living skills assessment system across all critical areas for functional living. Why the AFLS Works

Utilize Anytime, anywhere – The FLS spans all areas critical to the development of functional living skills (Basic, Home, School, Community, Vocational, and Independent)

Need Curriculum? Use the AFLS to Develop It! The AFLS supports and enhances any curriculum – no matter the mandated curriculum – the AFLS works with them all.

Easy to Understand – Written in practical non-technical language; no certification required.

Simple to Use – Complete with a Guide that provides step-by-step instructions with examples and methods making the system easy for all stakeholders

Affordable and Customizable – The AFLS is significantly less expensive than other autism assessment tools and users can customize their program to the needs of any learner at any time.

Our Ask:

Support Parents acquire skills to use the manuals. They work hand in hand with Occupational Therapists as a growth grid of acquired strengths towards independence.

Support Trainers understand the connection between Functional Living Skills and the teaching methodologies towards inclusion in the classroom using specific interests.

Support us fund learning support assistants to work with our teachers in the mainstream classroom.

Support us through scholarships to transition youth to Vocational training centres for their chosen career paths.

Tuleane Afrika Initiative (TAI)

Founder, Irene Muturi