Introduction

School feeding initiatives play a vital role in promoting students’ health, cognitive development, and overall academic performance. Proper nutrition is essential for brain function, concentration, and energy levels, making well-balanced school meal programs a key factor in educational success. Scholarly research strongly suggests that school feeding programs significantly contribute to enhanced learner participation, motivation, communication, and higher-order thinking skills. In regions affected by food insecurity, these initiatives serve as key interventions that not only nourish children but inspire learning and keep them in school. (WFP, 2021). Globally, over 100 countries have adopted school feeding programs, positively impacting 1.5 million children. Countries such as Japan, Finland, and the United States have well-structured school meal policies that ensure students receive nutrient-rich meals. The Global School Meals Coalition was established in 2021 to ensure that every child has access to school meals by 2030. For many children in sub-Saharan Africa, hunger is a major obstacle to education at the regional level. Nutritional deficiencies and food insecurity hinder a child’s learning capacity, underscoring the importance of school-feeding programs. The Home-Grown School Feeding (HGSF) program, backed by the African Union, connects local farmers with schools, improving child nutrition and supporting local economies. Countries such as South Africa, Ghana, and Nigeria have invested in national feeding programs that have increased enrollment, lower dropout rates, and improved student concentration.

Kenya’s School Feeding Programme (SFP) was initiated in 1979, providing milk packets to pupils, and was fully implemented in 1980 by the government in collaboration with the World Food Programme (WFP). The purpose was to improve the intellectual capabilities of school-going children. However, despite these efforts, the program did not achieve its full potential in many regions. In partnership with the WFP, the Kenyan government transitioned towards a government-led Home-Grown School Meals Programme (GoK, 2007; WFP, 2013). (HGSFP) which provides over 1.5 million children in food-insecure areas with daily nutritious meals, helping to boost enrollment, retention, and performance. This program has significantly improved student well-being, attendance, and cognitive function.

At the county level, Homabay County in Nyanza, Kenya, faces significant food security and malnutrition challenges. Various school feeding programs have been introduced to combat hunger and enhance student performance. The Home-Grown School Meals Programme has benefited many schools by sourcing fresh produce from local farmers, ensuring sustainability and economic growth within the community.

The Role of School Feeding Programs in Academic Performance

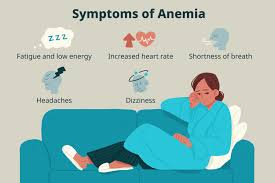

Academic performance refers to learners’ degree of accomplishment after undertaking an examination and attaining a graded position. Smilansky and Shefatya (2013) agree that academic performance typically is characterized by a combination of expertise, aptitudes, capabilities, attitudes, and comprehension attained by a student due to their active participation in a specific set of educational experiences. Research highlights that poor nutrition and health adversely affect cognitive abilities and learning capabilities (Bundy, 2018).

Countries with well-structured school meal programs report better academic outcomes, higher attendance, and improved concentration levels. In developed nations such as the United States and the United Kingdom, school meals are designed to ensure that children receive a nutritionally balanced diet. Research highlights that school meals contribute to better socialization, higher energy levels, and improved academic engagement.

Schools are essential for fostering healthy habits, given that children’s eating preferences frequently continue into adulthood. By including these programs in national safety nets, nations guarantee that children have access to healthy meals, enhancing learning outcomes.

Kenya has made substantial strides in school meal programs. The Kenyan School Feeding Programme (SFP), in collaboration with the World Food Programme (WFP), initially aimed to improve intellectual capabilities by providing food to school-going children. However, financial and logistical challenges hindered its full success. The program later evolved into the Kenyan Home Grown School Feeding Program (HGSFP), which was designed as a safety net strategy to increase food supply, improve incomes, and reduce hunger and malnutrition. The program was focused on making school feeding available to all schools nationwide, rather than just a select few. It also established connections with agricultural development agencies to facilitate the purchase and delivery of food from the local communities. The program not only tackled the nutritional and educational challenges faced by underprivileged children but also fostered a stable and reliable market for local small-scale farmers.

Two main food-for-education initiatives include:

School Feeding Programs (SFP): These provide meals during school hours to improve student nutrition and focus.

Take-home ration (THR) programs supply food to students’ households based on school attendance, encouraging enrollment and retention.

According to the National School Meals and Nutrition Strategy, school meals should be nutritionally adequate, socially acceptable, and practically feasible. The Home-Grown School Feeding Program (HGSFP) provides each child with a meal containing 706 kilocalories, 23 grams of protein, and 11 grams of fat—one-third of a child’s daily nutritional requirements. While these initiatives have achieved various successes, they still face threats from funding gaps and inconsistent food supply.

Tajizuri’s Contribution to School Nutrition in Homabay

Homabay County faces significant food insecurity and malnutrition, affecting students’ academic performance. Various school feeding programs have been introduced to combat hunger and enhance student performance. The Home-Grown School Meals Programme has benefited many schools, by sourcing fresh produce from local farmers.

The impact of these programs has been profound, with increased school attendance, better concentration, and improved academic performance among students. Cases of malnutrition, particularly in low-income households, have also decreased. However, challenges such as inadequate funding, logistical constraints, and food supply disruptions continue to threaten the sustainability of these initiatives. Organizations like Tajizuri have stepped in to support school feeding programs in Homabay. By working with local schools through its Lishe bora, Elimu bora Program, Tajizuri helps ensure that children receive nutritious meals, and nutrition supplements like Vitamin A improving concentration and academic success. Meals produced at school are intended to give energy for the mental and physical activities to the body and brain to function and enhance pupils‟ alertness during class hours. Through collaboration with communities and schools, Tajizuri has played a significant role in enhancing educational results and lowering malnutrition rates. Our efforts have improved schoolchildren’s cognitive performance, raised learner engagement, and decreased dropout rates.

Conclusion

Expanding school feeding programs is key in the fight against child hunger and malnutrition in low-income regions. Nutritious school meals are more than just meals; they represent an investment in education, health, and future productivity. A well-structured school feeding program can bridge learning inequalities, improve student performance, and contribute to national development. Building a healthier and more educated society requires strengthening these initiatives at all levels, from global, regional, national, and county.

Ensuring access to nutritious school meals for all children requires the joint efforts of governments, non-governmental organizations, and communities. After all, a well-fed child is a better learner, and that’s an investment worth making.

Prepared by:

Sabwili Mpoyana

Nutrition Associate

Reviewed By: Tatiana Nadongo